[purchase]

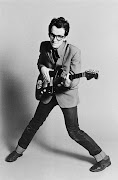

I’m currently reading Kenny Rogers’ new autobiography, Luck or Something Like It. If you’re into music history, it’s a very nice compilation of adages, lessons, experiences and memories along Rogers' road to stardom and fame.

In one anecdote, Rogers tells about how a friend from Mercury Records (Frank Luffell) came to his house to play the Roger Miller recording of a Mel Tillis song entitled, “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town.” One of the most powerful songs he’d ever heard, Rogers says “this soulful narrative became an anthem for the unseen victims of war, those who were injured but not killed. They were unnoticed and unheralded.”

I did a little further research on the song in the excellent book by Dorothy Hortstman entitled Sing Your Heart Out, Country Boy. She provides song lyrics and comments on them by the artists who wrote them, or a friend or heir. In the case of “Ruby,” Tillis says it was based on a true story of a man from his home town in Florida who had been injured during WWII in Germany and then sent to England to recuperate. He met and married a nurse. Back in the States, his health problems kept recurring, and he became temporarily paralyzed.

Tillis stated, “Ruby stood by him till she could stand it no longer. Then she started fixing her hair, putting flowers in it, painting her lips, and walking back and forth in front of the pool room. She was lonesome, needed attention. She was a good girl, actually, but the way I wrote it. I put the blame on her. At the time, I didn’t know what was going on because I was only 12 or 13 years old. Twenty-three years later, I realized what was happening. I just changed the wars and brought it up to date and wrote the story in about an hour. Eventually, it was a couple of years ago, he killed her and himself too. That’s a true story.”

Even though Kenny Rogers sings about “that old crazy Asian war” in the song, couldn’t it really refer to any conflict, as well as the torment and agony experienced by the bedridden or paralyzed war veteran? Having sung many classic story songs and ballads during his days with the New Christy Minstrels, Kenny Rogers admits a real affinity for the form and says that many of the most memorable songs in both pop and country are ballads like this (from the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” to Johnny Cash’s “A Boy Named Sue.”) Rogers declares that, “A story song, to have any impact, demands that you listen to the lyrics and imagine the scenario in your head.” “Ruby” and many other story songs launched Kenny Rogers. Essential listening of his repertoire includes “Lucille,” “The Gambler,” “Reuben James,” “Coward of the County,” and many more.

In his autobiography, Rogers declares, “I guess I was born to sing these kinds of plaintive, often tragic tales.” Because they also had another hit on the radio at the time (“Once Again She’s All Alone”), record producer Jimmy Bowen came up with the wise business decision of putting Kenny’s name in front of his band’s (First Edition) so as to separate the records and get airplay for both. With its topical war reference and tragic narrative about a forgotten solider, “Ruby” went to No. 2 on the charts. Kenny Rogers and The First Edition followed “Ruby” with another successful and compelling ballad called “Reuben James” about a black man raising a white child.